In this article by Nigel Davies, Director at Evolve Consultancy, the challenges and misconceptions surrounding digital transformation and compliance with industry standards are explored.

Nigel advocates for a pragmatic approach, emphasising the importance of focusing on practical solutions and effective information management over the overwhelming world of acronyms and semantics in the realm of BIM (Building Information Modelling).

No-one wants to follow standards.

Most people don’t even understand what “the standards” mean, and those that do will find that they often don’t seem to apply, or are so convoluted to be almost impossible to implement in a practical manner. Yet compliance with UK – and now international – standards is seen as a key ingredient of digital transformation and essential for maintaining competitiveness.

When we first speak to companies about their digital transformation, many are afraid; they look to the rosy picture being painted of “BIM level 2”, of “better information management” and “digital twins” and see themselves as well-behind the adoption curve – less bleeding edge, or even leading edge, but more like club-wielding Neanderthals, living off pure belligerence rather than having any identifiable strategy.

But often this is far from the truth. Understanding, and easy adoption, of digital processes is often due to misunderstanding the questions being asked – of blindly following a tick-box exercise rather than appreciating the realities, and necessities, of managing information.

Unfortunately in current times, it seems you are a self-proclaimed expert in BIM if you use as many acronyms as possible. Acronyms that no-one outside of BIM circles understands, or even cares about. This is not what expertise in BIM is. Expertise in BIM is being able to assist with delivering your company’s projects, whether they be small commercial buildings, larger residential schemes or super-sized infrastructure projects. It’s also about the ability to provide the end user with the sufficient information to operate and maintain their asset, not endlessly arguing the semantics of ISO 19650-2 clause 5.3.2 note 2 on X (formerly Twitter). We’ve lost sight of the goal.

That’s not helped by the shift towards the term “Information Management”, just as the rest of the industry is understanding BIM. While some would like to you believe that “BIM is dead” we’re still thinking idealism rather than pragmatism. Does it matter what it’s called? In the end, it’s called what the majority call it. It’s what it delivers that’s important. The mindset we need to break this that of BIM as a specialism, that Information Management is a topic solely for the BIM Coordinator. Yet in reality, BIM Coordination applies only to a small proportion of the ISO 19650-2 workflow.

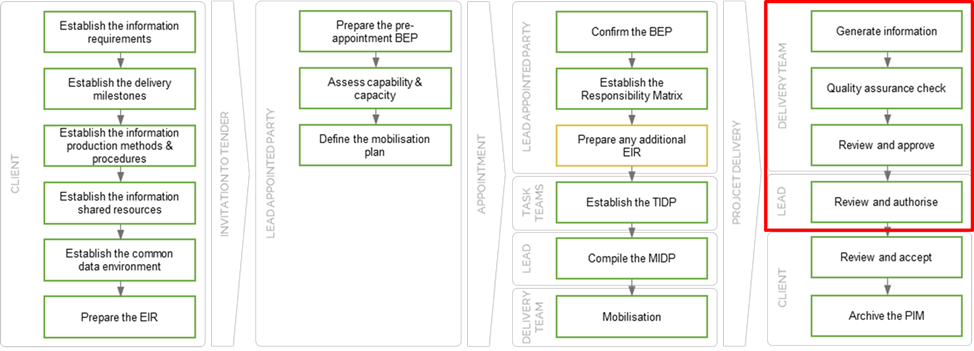

BIM Coordination really only applies fully to the parts of ISO 19650-2 highlighted in red.

Information Management applies to everyone at all steps from the inception through the final delivery and on into facilities management. That starts with the definition of clear information requirements.

Many projects we work on do not define what a maintainable asset is. Something so simple and so important to the operations of a building, and the design teams don’t even know what it is they need to provide data on. And even then, if defined, the delivery mechanism (COBie?) is much maligned and misunderstood that it becomes a theoretical stumbling block before it’s even mentioned.

What is a maintainable asset?

Part of this problem is due to the lack of definition of clear and unambiguous information requirements but part of it is also about providing as much help as possible. We – as an industry, not just the client – need to consider how to make this easier for all of us.

An example of this might be the use of different coding systems between design, construction and operations. Uniclass has become commonplace in project data. It is unusual now for us to receive models which don’t have classification codes already built in. But Uniclass is not common in facilities management. Other systems, notably NRM for costing or SFG20 for specifying maintenance and replacement schedules are more common. But SFG20 means nothing to a design team, and neither should it.

If you need SFG20, ask the design team for Uniclass and map the tables across to your CAFM system yourself. Yes, ideally these mappings would be available anyway, but that’s exactly what I mean when I say “we – as an industry”. And to achieve this, consistent Uniclass codes are needed. In reality codes are often assigned arbitrarily because the “best” search result doesn’t immediately show the hierarchical context. If you need consistency, specify which exact code you need to use in your information requirements. Simple.

That’s only one example of a pragmatic approach. Generally, we need to take a similar approach to all our BIM conundrums. If you ask the question “What do I need?” never follow it with “I’ll ask for everything just in case”. The best results come when you understand how to get what you need and who is best placed to deliver that. Start focussing on the pragmatic, not the semantic; on the quick wins, not the long-term aspirations; on listening to what people say, not dictating to them.

That’s how you’ll deliver “the right information to the right person at the right time.”

By Grace Donnelly

By Grace Donnelly